In a September 2021 letter to Senate leadership, President Biden’s first Border Patrol chief, Rodney Scott, complained that he was “sickened by the avoidable and rapid disintegration of what was arguably the most effective border security in” U.S. history in the prior few months. Successful immigration policies implemented by former President Donald Trump made that “effective border security” possible, so — why didn’t it last? To explain, I will start by describing the state of the border when Trump took office in January 2017, and in my next piece, illustrate the steps that he took to provide the security Chief Scott described, and that Biden was able to quickly undo.

“In the Beginning ...”. To start, you have to go back to shortly after the Border Patrol was formed in 1924. Concerned about a then-increase in illegal migration, Congress used the Labor Appropriation Act to take the loose cadre of border guards then assigned and create the component within the Department of Labor’s then-Bureau of Immigration.

The following year, FY 1925, agents apprehended just fewer than 22,200 illegal entrants at both the Southwest and Northern borders, as well as in Florida and along the Gulf of Mexico. Aside from a brief spike in FY 1929, when there were nearly 33,000 apprehensions, illegal entries thereafter remained well below 23,000 until FY 1944, when illegal entries started to soar.

Part of that increase was spurred by a need for labor during the Second World War to replace troops who had been sent to military service. In response, President Franklin Roosevelt created the so-called “Bracero Program” in 1942 to bring Mexican farm laborers to the United States, which remained in effect until 1964.

As the Library of Congress has explained, however, the program also “resulted in an influx of undocumented and documented laborers”.

With troops returned home from both World War II and the Korean War, Mexico facing its own labor shortage, and many farmers evading the wage and working conditions requirements set by the Bracero Program by hiring illegal migrant laborers, the Eisenhower administration initiated a deportation and border enforcement crackdown in the mid-1950s (which included more than a few documented abuses). By FY 1954, agents apprehended more than a million illegal entrants at the Southwest border.

Apprehensions dropped and remained below 100,000 in the 1960s until FY 1968. Including a few yearly blips, they slowly increased from there, and by FY 1983, yearly apprehensions reached more than one million, hitting a peak of nearly 1.7 million by FY 1986, with only subtle declines thereafter.

IIRIRA. Republicans retook control of the House of Representatives after four decades out of power in the chamber in the congressional elections of 1994, and gained a majority in the Senate. They quickly began reorganizing things.

One of the things congressional Republicans reorganized was border enforcement, culminating in passage of the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 (IIRIRA).

IIRIRA expanded the grounds of deportability and, most importantly from a border security perspective, eliminated the convoluted “entry doctrine”, which split border migrants into two groups — those who were “deportable” and the rest who were “inadmissible” — based on whether they had crossed free of “official restraint” (an often tedious and fact-specific determination). The latter group were given more due process rights, while the former had only those rights Congress had given them.

In place of that unworkable and bifurcated system, IIRIRA created a unitary process for expelling aliens from the United States known as “removal” and treated all illegal cross-border entrants and aliens deemed inadmissible at the ports as “applicants for admission”, subject to the same inspection protocols regardless of whether they had come free of official restraint or not.

Then, in section 235(b) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) as amended by IIRIRA, Congress gave border and port officers (including Border Patrol agents) a choice on how to deal with illegal migrants. Officers can either subject those aliens to “expedited removal” (at section 235(b)(1)), which allows them to remove those aliens without obtaining a removal order from an immigration judge or instead place them into “regular” removal proceedings (under section 235(b)(2)) in immigration court.

Expedited removal, however, comes with a “catch”: If an alien subject to that process claims a fear of harm if returned, or requests asylum, CBP must send the alien to a USCIS asylum officer who will interview the alien to determine whether the alien has a “credible fear” of persecution.

Credible fear is a screening process to determine whether an alien may be eligible for asylum, and thus most aliens receive “positive credible fear determinations”. By statute, aliens who receive positive credible fear determinations from an asylum officer (or immigration judge on the alien’s request for review, which the statute also provides for) are placed into regular removal proceedings to apply for asylum.

All of that said, Congress mandated in section 235(b) of the INA that regardless of whether CBP subjects aliens to expedited removal/credible fear or places them into regular removal proceedings, those aliens must be detained, from the moment they are encountered to the point at which they are either granted asylum or removed.

September 11th. While Congress in IIRIRA provided Border Patrol agents (in particular) the legal authority needed to respond to illegal migration, it didn’t give them all the resources they needed to do so. In FY 2001, for example, there were fewer than 9,200 agents to secure the 1,954-mile Southwest border — still more than double the agents there a decade before (4,139 in FY 1992) — but nowhere near enough.

That changed following the September 11th terrorist attacks, and by FY 2011 staffing levels had more than doubled (to 18,506 Southwest border agents). I’ll return to that below.

Border Releases and the Morton Directive. Despite the IIRIRA reforms and increased staffing, it took years for illegal entries at the Southwest border to decline. Southwest border apprehensions hovered around one million until FY 2007, when they dropped below 900,000. The IIRIRA reforms, coupled with increasing resources and the “Great Recession” of 2008, combined to drive Border Patrol Southwest border apprehensions down to fewer than 600,000 in FY 2009.

At that point, a level of complacency set it, and the Obama administration made a move that would trigger ever-higher levels of immigration.

In December 2009, Obama’s then-ICE Director, John Morton, directed his officers to release illegal migrants who received positive credible fear determinations into the United States under DHS’s “parole” authority in section 212(d)(5)(A) of the INA, notwithstanding the strict limitations Congress had placed on that power (also in IIRIRA), and despite the detention mandates in section 235(b) of the INA.

That directive had a devastating effect on border security, but the impacts were incremental. In fiscal years 2006 through 2009, before that pronouncement went into effect, just between 4 and 5 percent of all aliens subject to expedited removal — fewer than 5,400 aliens annually — claimed credible fear.

Credible fear claims grew to nearly 9,000 in FY 2010 (7 percent of aliens subject to expedited removal), and to almost 12,000 in FY 2011 (8 percent), before jumping to more than 36,000 (15 percent of the total) in FY 2013. It took a while for smugglers to catch onto the scam, but once they did, it plainly featured prominently in their illicit sales pitches.

By FY 2016, nearly four in 10 (39 percent) aliens subject to expedited removal at the Southwest border — more than 94,000 illegal migrants all told — were claiming credible fear.

That release policy also generated a deleterious shift in the demographic makeup of illegal border crossers. Few Mexican nationals have legitimate persecution claims, so few bother to ask for asylum even though as recently as FY 2010, nearly 90 percent of all aliens apprehended at the Southwest border were from Mexico.

In FY 2014, however, the makeup of nationals apprehended at the U.S.-Mexico line shifted. More than half (52 percent) of illegal entrants nabbed there that year were “other than Mexican” (OTMs), and nearly all (94 percent) of those 252,000-plus illegal OTM entrants were nationals of the “Northern Triangle” countries of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras.

Many were released after passing the credible fear test, which encouraged more of their countrymen to come and exploit this loophole. By FY 2019 — a year in which agents apprehended nearly 852,000 illegal entrants at the Southwest border — more than 71 percent of them (600,000-plus individuals), were from the Northern Triangle.

Few were ever granted asylum, however. That fiscal year, DOJ revealed that immigration judges granted asylum to just 8 percent of Salvadorans, 5 percent of Guatemalans, and 3 percent of Hondurans who had been stopped at the borders and ports and claimed a fear of return. Still, they were allowed to spend years living and working here, and few were ever forced to leave.

Flores and “Family Units”. That rush of OTM illegal entrants from the Northern Triangle was not the only demographic border shift that began under the Obama administration, as the number of adult aliens who entered illegally with children in “family units” or “FMUs” also surged.

Prior to FY 2013, illegal FMUs entries were not a common phenomenon, likely because adults recognized that it was criminally reckless to bring a child on the exceptionally dangerous trek to the Southwest border of the United States.

As the Congressional Research Service (CRS) explains: “Single adult migrants have long dominated apprehensions at the Southwest border. As recently as FY2012, single adults made up 90% of these apprehensions.” By comparison, just 3.1 percent of illegal migrants came in FMUs that year.

Still, it was by then enough of a phenomenon for CBP to start keeping stats on family unit entries in FY 2013, when just fewer than 15,000 of the more than 414,000 aliens apprehended by Border Patrol at the Southwest border (3.6 percent) were in FMUs.

That quickly changed the next fiscal year, when more than 68,000 aliens in FMUs (many adult women travelling with children) were apprehended at the Mexican border, 14.2 percent of all apprehensions that year. Most were OTMs.

Obama was quick to act shortly after this new (and especially vulnerable) cohort of migrants started showing up, announcing in August 2014 that ICE would open up family detention facilities in Artesia, N.M., and the Karnes County Residential Center in Texas “to detain and expedite the removal of adults with children”.

It worked to a degree, and fewer than 2,800 of the nearly 30,000 illegal migrants apprehended in March 2015 (9.3 percent) were in FMUs.

But it wouldn’t last.

In 1997, the Clinton Justice Department had entered into a settlement agreement in Flores v. Reno, closing over a decade of litigation over the terms and conditions of the then-INS’s detention and release of alien children.

I was at the INS at the time and have no idea why DOJ settled with the Flores plaintiffs, given (1) they had fought the case — largely successfully — for more than 12 years at that point, and (2) as related to illegal entrants, the agreement violated the detention mandates in section 235(b) of the INA. Still, as it was commonly read as applying only to “unaccompanied” children without parents, Flores did little harm.

As least at first. Then, in May 2015, the Flores plaintiffs filed a motion with Judge Dolly Gee of the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California to enforce the agreement with respect to both the adults and the children in FMUs, in a case captioned Flores v. Lynch.

They asserted that Obama’s ICE was in breach of the agreement because it had adopted a no-release policy for migrant families, and because ICE’s family detention facilities did not comply with a requirement in the agreement that required DHS to hold children in state-licensed facilities (there is no federal licensing scheme because outside the immigration context, the federal government doesn’t detain children).

In August 2015, Judge Gee issued an order directing DHS to release all migrants (children and adults) in FMUs within a (wholly arbitrary) 20-day timeframe. Obama’s DOJ appealed her order to the Ninth Circuit, which in July 2016 limited it to just the FMU children. To avoid allegations of “family separation”, however, DHS has since usually released both adults and children in FMUs together.

Notably, the Obama administration did not seek Supreme Court review of Flores, although it plainly disagreed with Judge Gee and the circuit court.

The results were predictable, and in both FY 2016 and FY 2017, Border Patrol agents at the Southwest border apprehended more than 75,000 illegal migrants in FMUs — 19 percent and 25 percent of total apprehensions those fiscal years, respectively.

Likely the most significant implication of Flores, however, was that ICE stopped investing in housing for aliens in family units. By FY 2019, there were just 2,500 daily spots available to house family migrants in, total, even as tens of thousands of FMUs poured across the border monthly.

Border Patrol Staffing. Another area in which both the Obama administration and Congress grew complacent was Border Patrol staffing.

From a peak of more than 18,600 agents at the Southwest border in FY 2013, the cadre dropped below 18,000 agents in FY 2015 (17,418, a 6.4 percent decline in two years), and then below 17,000 in FY 2016 (16,605, an 11-percent decline in four years).

D.C. decisionmakers apparently decided that the declines in illegal entries in the early 2010s were permanent, and not a temporary blip, and that agents were a luxury the taxpayers could not afford. History has shown they wrong, on both counts.

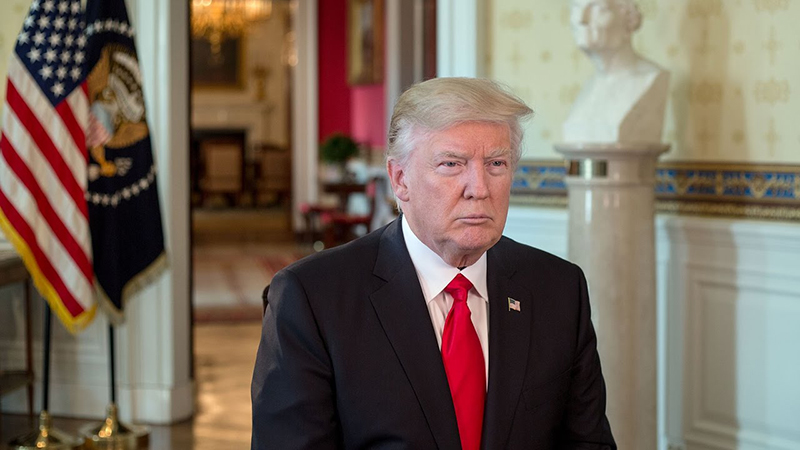

Candidate Donald Trump. Trump made illegal immigration generally and border security specifically a cornerstone of his 2016 presidential bid.

In an August 2016 speech in Phoenix, Ariz., for example, he blamed Obama and his own Democratic opponent, Hillary Clinton, for “engag[ing] in gross dereliction of duty by surrendering the safety of the American people to open borders”, vowing instead to “build a great wall along the southern border” and “end catch and release”.

That followed statements that Trump had made in the fifth GOP debate in December 2015 in Las Vegas, Nev., where he explained:

I have a very hardline position, we have a country or we don’t have a country. People that have come into our country illegally, they have to go. They have to come back into through a legal process.

I want a strong border. I do want a wall. Walls do work, you just have to speak to the folks in Israel. Walls work if they’re properly constructed. I know how to build, believe me, I know how to build.

I feel a very, very strong bind, and really I’m bound to this country, we either have a border or we don’t. People can come into the country, we welcome people to come but they have to come in legally.

The next candidate to speak, former Florida Governor Jeb Bush (R), who was asked by the moderator: “Listening to this, do you think this is the tone — this immigration debate that Republicans need to take to win back Hispanics into our party, especially states like where we are in Nevada that has a pretty large Hispanic community?”

Bush's answer:

No it isn’t, but it is an important subject to talk about for sure. And I think people have good ideas on this. Clearly, we need to secure the border. Coming here legally needs to be a lot easier than coming here illegally.

If you don’t have that, you don’t have the rule of law. We now have a national security consideration, public health issues, we have an epidemic of heroin overdoses in all places in this country because of the ease of bringing heroin[] in. We have to secure the border.

It is a serious undertaking and yes, we do need more fencing and we do need to use technology, and we do need more border control. And we need to have better cooperation by the way with local law enforcement. There are 800,000 cops on the beat, they ought to be trained to be the eyes and ears for law enforcement for the threat against terror as well as for immigration.

GOP voters chose the former tack and tone over the latter, or as the political analysis website FiveThirtyEight explained in a postmortem of the 2016 election, “immigration may have been the issue most responsible for Trump’s winning the Republican nomination. In every state with a caucus or primary exit poll, he did best among voters who said immigration was their top issue.”

Push and Pull Factors. Immigration generally, and illegal immigration in particular, is driven by both “push” factors and “pull” factors.

Push factors describe the reasons why foreign nationals leave home, things like war, instability, poverty, crime, corruption, “food insecurity”, poor educational opportunities, and inadequate healthcare.

Pull factors, conversely, are the reasons that those foreign nationals go to specific receiving countries. Lavish social benefits — where available to newcomers — are on the list, to be sure, but so are greater employment opportunities, better schools, safer communities, and a more secure rule of law. And the opportunity to reunite with family.

Enforcement policies trump both push and pull factors. East Germany (famously) had a massive wall (the Mauer) blocking transit to the west, and border troops (Grenztruppen) there had orders to shoot to kill anyone who tried to get past. Workers in Dresden (in the east) would have had more freedom and made much more money in Munich (in the west), but the odds of making the trip were low, so relatively few (about 100,000 in a population of around 17 million) tried.

The effects of enforcement are even more marked on the pull side of the ledger. A country that strictly enforces its border to illegal entries (like Israel) receives fewer irregular migrants, blunting both push factors and internal pull factors.

Logically, but still somewhat counterintuitively, the absence of a vigorous border enforcement regime magnifies the attractiveness of internal pull factors, “akin to posting a flashing ‘Come In, We’re Open’ sign on the ... border”, as one jurist put it recently.

When it comes to the rate of illegal immigration, border policy and immigration enforcement are paramount. In my next post, I will explain how President Trump’s policies influenced the rate of illegal entries, and why those policies didn’t last.