Download a PDF of this Backgrounder

David North is a Senior Fellow at the Center for Immigration Studies. He has been studying various migration streams, both of immigrants and nonimmigrants, off and on since 1969. He is grateful for the research assistance of Dylan E. Thomas, a CIS intern.

The term "most favored nation" is left over from history's debates on tariff and trade policies, but the concept — we treat some nations more generously than others — can easily be applied to America's crazy-quilt collection of immigration policies.

In the old days (the 1920s to the mid-1960s), the nations of northern and western Europe were specifically given far larger immigrant quotas than nations elsewhere in the world. That was written in law, and was quite controversial until it was overturned during the LBJ administration.

The 1965 amendments to the Immigration Act eliminated the country-of-origin quota system, replacing it with a structure that favored family immigration (i.e., a preference for relatives of other recent immigrants) and drastically expanding the inflows of migrants; this admission system is still in place and favors entrants from nations in Asia and Latin America.

Meanwhile, almost invisibly, a third pattern is starting to emerge, mostly in the field of (at least nominally) temporary migrants, in which certain nations are favored indirectly by a combination of forces: our immigration laws and economic and other variables in specific migrant-sending nations. Before we delve into these emerging patterns, let's briefly review the results of the first and the second patterns in terms of favored nations.

The First System: Country Quotas

Following World War I, after decades of massive immigration intakes and at a time when the nation's mood was to withdraw from the world, a Warren G. Harding-era Congress voted to put numerical limits on immigration (a very good idea) and to allocate most of the remaining visa slots according to the nation of origin of the arriving immigrants (a bad idea). The formula used for the allocation of quotas was based on the ethnic ancestry of the American population in 1890, before the waves of migration from southern and eastern Europe, so it was tilted toward northern and western Europe.1

Since this was a piece of immigration legislation and thus was subject to the usual pressures of special interests, and since it was fiddled with, but not fundamentally changed over 40 years, all immigration was not controlled by the country-of-origin quotas. The biggest gap, and one hard to fathom at this point in time, was the total absence of any numerical controls on migration from the Western Hemisphere. This was not an early triumph of the Hispanic lobby,2 it merely reflected limited migration from that part of the world and the relatively modest population then of that hemisphere.3

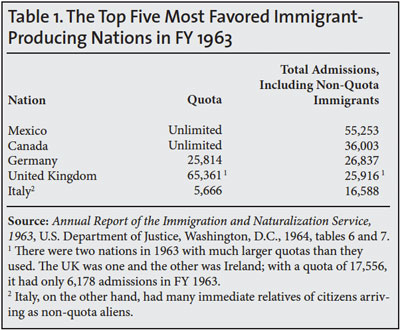

In this legislation there were also provisions for the non-quota admissions of immediate relatives of U.S. citizens, and by 1963 several WWII provisions for small, specific groups of refugees had been added. In 1963, just before the law changed, there were 306,260 admissions, divided as follows:

- Quota immigrants: 103,036

- Non-quota, Western Hemisphere: 147,724

- Non-quota, immediate relatives: 30,606

- Non-quota, ministers, refugees, and others: 24,894

Within this setting there were five leading nations of immigration, as shown in Table 1.

The residents of four of the five top nations were of European origin. There were no nations among the five from Asia or Africa. These, then, were the favored nations as the old system died.

The Second System: Mostly Family Members, Some Workers, Some Refugees

The country quotas had long been controversial, being seen as racist by many, but it took the lopsidedly Democratic Congress elected with Lyndon Johnson in the fall of 1964 to change things. This was, after all, the era of Civil Rights legislation.

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 was managed by Sen. Philip Hart (D-Mich.) and the then-young Sen. Edward Kennedy (D-Mass.) in the upper chamber and by Rep. Emmanuel Celler (D-N.Y.) in the lower one. Celler was the long-time chair of the House Judiciary Committee, and had been a persistent critic of the national-origin quota system for many years.

My sense has always been that the reformers, who finally dumped the quotas, were so focused on eliminating that system that they did not pay much attention to the essential follow-on question: If the nation is to continue to have numerically limited immigration, as was the prevailing sentiment, what formulae should be used to allocate the limited visas?

The resulting law, as amended many times during the following years, produced a system in which much of immigration was numerically limited, but not all, with a heavy emphasis on would-be immigrants who already had relatives in the United States. There were also allocations of visas to "needed" workers of several kinds, and their relatives, and varying numbers of visas were made available to refugees (who could, of course, in subsequent years, successfully seek the admission of their relatives),

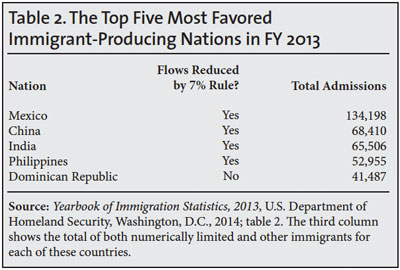

Congress, worrying that some nations could flood the resulting system despite the overall numerical limits, added a provision that no single nation could have more than 7 percent of the numerically controlled visas. This has lowered the number of entrants from four countries (Mexico, China, India, and the Philippines) and has built up large waiting lists of people (many already in this country in non-immigrant status) seeking both worker and family visas. There are waiting lists, but shorter ones, for people from other nations.

The current most-favored nations are those four plus the Dominican Republic, as Table 2 shows.

Note that no European nations are on the list anymore, and that three of the five were, a couple of hundred years ago, parts of the Spanish Empire.

The Emerging Pattern: Specialty Migration Streams

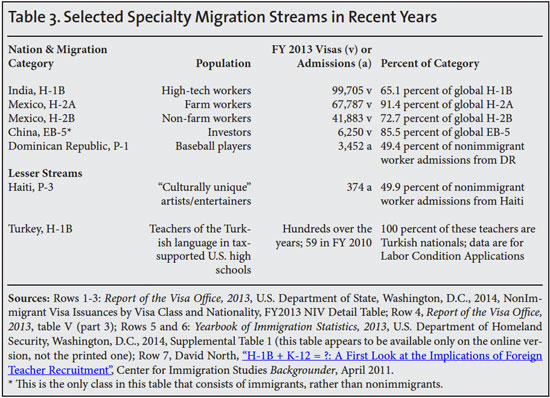

There are probably scores of specialty migration streams currently, all different from the family migration-dominated norm. I have selected seven as particularly significant or intriguing. They should be regarded as a non-random sample of these populations, and are listed below.

In each of these seven streams there is an unusual concentration of migrants by nation of origin, and each of these concentrations relates to a specific, often quite narrow, provision in the immigration law. In all but the EB-5 program (for immigrant investors) the migrants are at least nominally temporary ones.

In the largest five streams shown in Table 3, the aliens coming to this country (while they may not be really needed workers or investors) are, at least, playing recognizable roles in the American economy; but the last two streams seem to consist of totally artificial flows, created in response to quirks in the law and ethnic considerations, rather than to basic economic forces.

Nonimmigrant Worker Programs in General

We will examine each of the seven streams individually, along with the segments of the immigration law that facilitate each cluster of admissions, but before doing so, a general note about nonimmigrant worker programs is in order.

There are lots of these programs, all with combinations of letters and numbers related to provisions in the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA).4 Each was created to meet a specific set of perceived needs, and little effort has been made to create a grand, interrelated program to harmonize and rationalize the programs. Each was started at a different time. Each of the programs has a different set of laws and regulations, and these provisions are likely to remain unchanged for decades at a time because Congress moves slowly and regulation writers only slightly less so. Some of the programs have numerical limits on the number of annual admissions, some do not.

All of the programs are national in focus; they do not follow any international patterns or relate to any broad international agreements.5 All are designed to meet the needs of American interests (often as described by lobbyists) and rarely those of the temporary alien populations. However, it is also true that some of the more canny migrants, and their lawyers, have found ways to turn the existing rules to their own benefit in individual cases.

These seven quite different programs, however, have three basic elements in common:

First, six of the seven programs, by definition, are non-permanent in character; if one has a visa from a nonimmigrant worker program it is for a finite amount of time and ultimately it will need re-authorization.

Secondly, to a greater or lesser extent, those participating in these programs want to be, and sometimes can be, converted (the legal term is "adjusted") to permanent resident or green card status. This is relatively easy to arrange in some programs, virtually impossible in others.

Finally, in all seven of the streams we are dealing with — and in virtually all nonimmigrant worker programs in general — there is a legal need for a specific American institution of some kind to formally request that the migrant be admitted to this country. The role of these requesting institutions is not only crucial, it can vary tremendously; sometimes it can be benign, often it can be exploitative, and sometimes it seems to combine both of these characteristics.

In each of the sketches of the seven programs we outline the nature, level, and locus of exploitation because the degree and the kind of exploitation vary considerably from program to program. Most of the exploitation within these programs is along cross-ethnic lines (i.e., non-aliens exploiting aliens) but some of it is intra-ethnic, in that it involves one group of aliens exploiting another group of aliens, usually of the same ethnicity.

In all of these programs, other than the one dealing with Haitian entertainers, we should remember that there is another large social issue: the displacement of resident workers (citizens and green card holders) who could be (and I would argue, should be) doing most of the work in question.

Were the rules different (or more vigorously enforced), and were employers treated by our government as something short of gods, or at least archbishops, then most of the work done in these seven streams would be done by legal residents of this nation.

We now turn to the individual streams of interest.

India (H-1B) High-Tech Workers

The largest, most visible, and perhaps most controversial of the streams is the steady flow of Indians bearing H-1B visas to the United States. It is the only one of the seven streams that gets more than a passing mention in the press, and its preservation keeps large numbers of advocates, lobbyists, and their allies busy year-round.

The H-1B program is for the admission of high-tech workers to the United States. A bachelor's degree, and sometimes more, is required for these positions.

Most H-1Bs work in computer- or engineering-related jobs. Most of the H-1Bs are from India, a country that provides decent college educations, often in high-tech subjects, for many more people than it can employ in jobs needing that education. And the instruction is in English. These two factors, together with the desire of many U.S. employers to pay below-market-level wages for market-level talent, has fueled the growth of the H-1B program and caused a majority of the admissions to go to residents of the subcontinent.

There is, incidentally, no shortage of American high-tech workers as the industry argues, sleekly and consistently, and as many politicians believe.6 The attraction of the Indians is that they are eager to work at the wages offered, they are young, they are (because of the inner workings of the H-1B scheme) docile, and most of them speak fluent English.

The Process. How these basic factors play out in the H-1B admissions process is a complex story and routinely involves three federal agencies, the Departments of Labor (DoL), Homeland Security (DHS), and State (DoS).7

The American employer first has to file a Labor Condition Application (LCA) with DoL to satisfy the government that the job is appropriate for the program. The next step involves DHS; it must evaluate the petition and apply the H-1B numerical limits (to be discussed later). If the petition is approved by DHS, it is sent to the alien's home country and then the applicant (usually a male) seeks a visa from the nearest office of the State Department. It is up to the diplomats to figure out if the alien qualifies for the job and a visa. The final step involves very few rejections and that is when the alien, with the visa and his nation's passport in hand, is admitted to the nation by an inspector (working for DHS) at an airport. It is also possible for an alien, already in the United States, to obtain an H-1B visa-like document without leaving the States.

This is one of the streams of interest (the others are H-2B and EB-5) in which there are numerical limits on the number of admissions. Currently there is an annual 65,000 ceiling for bachelor's level H1-B workers and an additional one of 20,000 for aliens with U.S. graduate degrees (in science and engineering). Certain other employers may bring in H-1Bs outside the ceilings, including government agencies, academic institutions, and organizations whose workers are employed in academic settings.

These are the initial limits (which many employers complain are too restricted); extensions of visas are not counted against the ceilings. So there are about 100,000 H-1B arrivals a year.

Initial visas secured through this process are usually good for three years and are routinely renewable for another three years. Further, a worker whose employer has filed a green card petition for him, as many do, may extend his or her H-1B status beyond the six years, even though the approved petition is unlikely to produce an immigrant visa for many years to come. These six-year-plus extensions are usually issued one year at a time and are virtually automatic.

The Numbers. Given the ease with which H-1B visas can be extended, it is clear that there are many more H-1B workers present than the 100,000 or so new ones admitted each year. Bearing that in mind, it is troublesome that the government has never even tried to estimate the total size of the resident H-1B population. How many are there?

A few years ago I estimated that there was a population of some 650,000 or so H-1B workers in the nation as of September 30, 2009.8 Assuming a modest net addition of 50,000 a year since then, the total, as of fall 2014, would be about 900,000. (I cite my own estimate not because I think it is the best available, but because it is, sadly, as far as I know, the only one available.)

As noted earlier, in FY13, a typical year, 65.1 percent of the new visas were granted to Indian nationals. Applying 65 percent to 900,000, we get an estimate of 585,000 Indian H-1Bs, a population that dwarfs the totals of all the other six streams put together. The number is for all H1-Bs from India; a large majority of them, but not all, are in the IT business.

Institutional Arrangements. The interwoven, massive institutional arrangements for the perpetuation and expansion of this H-1B flow remind me of the most fearsome of medieval castles — sturdy, thick walls of stone; battlements; moats; archers; and pots of boiling oil poised at the top of the walls. Each defensive device is formidable in and of itself, and each effectively supports all the others.

These H-1B arrangements include soft-on-employer provisions in the immigration law itself; the aggressively supportive government of India that regards the H-1B program as a holy, civil right for its college graduates; the many direct, often India-owned, employers of the H-1Bs in the United States that profit from the system; the indirect users of these workers, including many of the giants of American industry; the educational institutions both here and in India that train these workers; the immigration bar; legions of the best-paid lobbyists in Washington; a cottage industry of academic supporters of the program, such as those with the Brookings Institution and the National Science Foundation; and, of course, the politicians who listen to all those other members of the Establishment who are sure that there is a shortage of high-tech workers.

This creates a powerful coalition in support of the H-1B system.

One of the nearly invisible buttresses of the program is built into the law itself, the five-step process that creates a climate of indenture.

The H-1B visa is often the third (and longest-duration) step in a five-step progression for these workers. Many arrive in the United States as F-1 students in undergraduate or graduate tracks (mostly master's students among the latter). After they secure the degree, they then obtain a modification of the F-1 visa, the OPT (Optional Practical Training) permit, an extension of the F-1 for up to 29 months, which allows recent foreign graduates to work in America — with both employer and employee free of payroll tax requirements. Then, many of the former OPT workers become H-1Bs, a status that goes on for years, particularly if they persuade their employers to file green card petitions for them.

Because of both the previously mentioned per-country immigration limits and the ceilings for what are regarded as needed workers, the wait for a green card for the Indian H-1B workers can be a long one: 5.5 to 11 years, depending on whether they are in the second or the third class, respectively, of the employment-based visas, according to the October 2014 issue of the State Department's Visa Bulletin.9

During the nearly 2.5 years in OPT status, and the much longer stay as H-1Bs, the workers remain docile and diligent (as they do not want to irritate an employer who has the power to grant a longer, legal stay in the country). An H-1B is nominally free to move from one employer to another in that status, but if a green card is the goal, it usually means that the process must be started all over again with the new employer.10 The green card is the fourth step along this path, and citizenship is the fifth step for many, but not all.

Locus of Exploitation. A large portion of the Indian H-1Bs work for Indian outsourcing companies; as a matter of fact, according to the MyVisaJobs.com website, the three largest employers of H-1Bs in the United States are Infosys, Tata Consultancy Services, and Wipro, all headquartered in India.11

Infosys has been frequently sued by U.S. workers for its labor practices,12 Tata Consultancy is a wing of the huge Tata Group, which also make automobiles, and Wipro started as the Western India Vegetable Products Limited. Many of the next dozen or so firms on the MyVisaJobs list are also Indian-owned. (The list, incidentally, is based on DoL records.)

It is generally agreed by those who have studied the matter (save those funded by industry), that the H-1B program reduces wages below what the market would demand and causes a situation that puts "guest workers in a precarious position that invites their exploitation, creates insecurity for them, and undermines the integrity of the labor market," to quote Ron Hira, associate professor of public policy at the Rochester Institute of Technology.13

There is agreement on the general economic impact of the H-1B program, but there is no agreement as to whether the Indian outsourcing companies are more exploitative than the major U.S. firms like Microsoft, Intel, and Google. Setting that controversy on wage levels to one side for the moment, it is clear (as can be seen by Tables 1A and 2A in Hira's cited article) that the Indian firms are far less likely to offer green cards to their workers than the big American companies, which I view as a serious stain on the Indian companies.

While the story of earlier arrivals exploiting later (and more naive) migrants from the same country is an old and dishonorable one, I know of nothing as extensive and well-organized as the manner in which these Indian firms are using an American law to exploit their own people via the H-1B program. There is nothing comparable in any of the other six specialty migration streams we are describing.

Mexican (H-2A) Farm Workers

The specialized flow of non-immigrant Mexican farm workers has the most seniority in terms of tradition and immigration history.

The H-2A provision in the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) creates a class of nonimmigrant workers who take temporary (often harvest-time) jobs on American farms; many of these workers arrive for the season and then return to Mexico during the winter. The provision (then H-2) dates back to WWI and was used initially to bring Jamaican workers to East Coast farm jobs, while illegal Mexican aliens did the same kind of work in the West.

During and after WWII, many of the movements of the Mexican nationals were legalized and channeled into the government's Bracero program. This operation, once involving as many as half a million workers and widely regarded as exploitative, was terminated on January 1, 1965, killed by many of the same political forces that ended the country-of-origin quota system. Subsequently, legal, short-term farm worker migrations were steered into the H-2A program.14

Some Jamaicans are still in the program, which is otherwise dominated by Mexican nationals; more than 90 percent of the 2013 admissions were Mexicans.

In addition to this legal flow of temporary farm workers, there is an extensive illegal flow of illegal aliens in the same industry, and from the same nation. Many of the latter now live in the United States year-round.

The admissions process for the H-2A farm workers is considerably less complex than it is for the H-1Bs. H-2A workers tend to come back year after year, often requested by name by employers. Unlike the EB-5 and H1-B programs, there is no visible passage from the first visa to the green card stage. As a result, many of the H-2A workers, like the Braceros before them, drop into illegal status as their technique for staying in the United States.

Locus of Exploitation. In the case of the farm workers, exploitation is mostly cross-ethnic, it is done by U.S. growers (often corporations) who pay the H-2A workers less than they would have to pay were they to hire on the open market. Sometimes bribes paid to local Mexican officials are needed for initial recruitment into the program, but my sense is that this is the lesser exploitation in this program.15

While there are some exploitative farm crew leaders of Mexican descent or birth, there are no major Mexico-related corporations — unlike the pattern with the H-1Bs — that exploit these farm workers on a massive scale.

Mexican (H-2B) Unskilled, Non-Farm Workers

The H-2B program is very much the smaller, not-quite-so-rural brother of H-2A.16 The work is supposed to be unskilled and temporary or seasonal and, as in H-2A, much of it is outdoors. This program is operated primarily by the Department of Labor, as is H-2A.

The top certified occupation in FY2012 was landscape laborer, with 24,094 positions; this was followed by forest worker, at 7,522; and amusement park worker, at 5,125. No other occupation was held by more than 5,000 workers according to the department's FY2012 report.17 Other occupations include housekeepers, waiters and waitresses, and tree planters. Some seasonal resorts rely on it for short-term staff.

For a more detailed analysis of this program, and its many problems, one can read the CIS Backgrounder by my colleague, David Seminara, "Dirty Work: In-Sourcing American Jobs with H-2B Guestworkers".18

As in the H-2A program, Mexico dominates as the prime source of workers for this program, though not as overwhelmingly. More than 70 percent of the H-2B admissions in 2013 were recorded as Mexicans. Two of the reasons, in addition to tradition, for Mexico's dominance in the H-2A and H-2B programs are because that nation is both nearby (thus travel is less costly), and it is poor (unlike Canada). Travel costs are supposed to be borne by employers.

There are currently non-controversial numerical controls on this program, with an upper limit of 66,000 per year. I have noticed (unlike the H-1B programs ceilings) no vigorous efforts to either raise or lower these limits, though, as shown below, at one point Major League Baseball was impacted by the limits and managed to get them changed.

Locus of Exploitation. The pattern, again is cross-ethnic, and closely resembles that of the farm worker program.

Chinese (EB-5) Immigrant Investors

While there is a heavy nation-of-origin concentration in this program, as in the other six streams, it differs from the others in a number of ways:

- It is a program for intending immigrants, not nonimmigrants.

- The EB-5 (for Employment-Based) program does not deal with workers at all, it deals with alien investors whose money is supposed to, and sometimes does, create jobs for American workers.

- Finally, unlike the other programs, those who may be exploited in the program are the rich. In fact, in some cases in which the foreigners are badly treated by U.S. middlemen the aliens are considerably wealthier than those who may be abusing them.

For many years the EB-5 program was under-utilized but the Obama administration has been an enthusiastic supporter of it and has made a number of changes in a successful attempt to expand it.19 One of the reasons I sense for this boosterism is that, unlike the vast majority of immigration programs that Obama wants to expand, this one, and the nonimmigrant H-1B program, both tend to bring in people with above-average incomes.

EB-5 offers aliens with half a million dollars to spare an opportunity to place that sum in a DHS-approved (but not guaranteed) investment; if the investment stays in place, the investor, the investor's spouse, and all of their under-21 children are given green cards at the end of two years. These half-million investments are placed through regional centers that are routinely private, for-profit entities that have been licensed by DHS. (There is also a million dollar option that does not involve the regional centers, but this is rarely used.)

DHS treats the regional centers permissively, and there have been numerous resulting problems; as Peter Elkind, editor at large for Fortune, put it recently:

But because the EB-5 industry is virtually unregulated, it has become a magnet for amateurs, pipe-dreamers, and charlatans, who see it as an easy way to score funding for ventures that banks would never touch. They've been encouraged and enabled by an array of dodgy middlemen, eager to cash in on the gold rush. Meanwhile, perhaps because wealthy foreigners are the main potential victims, U.S. authorities have seemed inattentive to abuses.20

These problems, such as bankruptcies and swindles, while not universal, have been particularly prominent in South Dakota recently, where they became a major issue in the 2014 Senate race.21

Despite the bad press and the massive EB-5 scam in Chicago that Elkind described in his article, wealthy Chinese continue to pile into the program, so much so that both the 10,000 EB-5 visa limit is about to be reached, and the former, ready availability of visas for Chinese investors is now in question.22

Why is this the case? And why are these visas particularly attractive to the Chinese? As noted in Table 3, 85.5 percent of the global issuances of EB-5 visas in 2013 went to Chinese nationals.

In general terms, the world's elite do not migrate; they stay at home and enjoy their money and their privileges where they grew up. But the Chinese rich, many of them newly affluent, are in a different situation. Many of them have lots of money, but lack a sense of security; they want a second passport, an international escape hatch that will allow them to emigrate from China, quickly if need be.

The EB-5 program, with its offer of a family-sized-basket-full of green cards for half a million dollars, fills that need neatly. America is an attractive alternative home, and the price is considerably lower than that demanded by most other nations with immigrant investor programs. Over and above the $500,000 investment, the investors also pay fees both to the regional centers, averaging perhaps $50,000 per investment, and to lawyers. These fees are not regulated by DHS or any other government agency.

Locus of Exploitation. As a result, many rich Chinese buy into the program, and do not pay much attention to the financial consequences of their investments. It is the set of green cards that attracts their attention, and this opens the way, as Elkind puts it, for the dodgy middlemen (virtually all of them Americans) to prey on the Chinese investors. So this is, again, a case of cross-ethnic exploitation.

Dominican (P-1) Baseball Players

P Visas, Generally. Before we get to the baseball players, it would be helpful to review the P nonimmigrant worker visa, generally. There are four subclasses:

- P-1 is for athletes, either as members of a team or as individuals;

- P-2 is for artists and entertainers working "under a reciprocal exchange program", a rarely used category;

- P-3 is for artists and entertainers working "under a program that is culturally unique"; and

- P-4 is for relatives, managers, aides, and servants of P-1s through P-3s.

Everyone in the first three subclasses is supposed to be of such prominence that they are "internationally recognized", a subject to which we will return. There are no numerical limits to this program and, in FY 2013, there were some 107,000 admissions in the first three classes.

On average worldwide, the P category is not used extensively. The total number of admissions of temporary workers and their family members — there are not a lot of the latter — came to nearly three million in 2013 — of these only 3.6 percent were in the P categories.

Looking over these numbers, nation by nation, what struck me as odd were two remarkable concentrations within the nonimmigrant worker flows, both related to the two halves of the same island, Hispaniola. From the eastern part, the Dominican Republic, 49.8 percent of the nonimmigrant workers coming to the United States were in the P class, while in the western (and much poorer) part, Haiti, the comparable percentage was 58.5 percent.23 Why should the P category percentages in both places be 13 to 16 times those in the rest of the world? What's going on?

We have better answers for the Dominican side of the island than for the Haitian side.

P-1 and Baseball Players. The overwhelming majority of the P class aliens from the Dominican Republic are in subclass P-1, and they are baseball players. (See Table 4.) More specifically, they are largely farm team players hoping for — and sometimes reaching — the major leagues. Think about the minor leaguers in the film "Bull Durham", but bear in mind that the dialogue would have to have been in Spanish. Presumably the large majority of the players, those who do not make the "big show", are supposed to return to the Dominican Republic; the more successful ones move into other immigration categories. The backstory here has been told by Joe Guzzardi, who is probably the only baseball writer in the world who is also a dedicated immigration restrictionist. He writes, in an article entitled "Playing Major League Baseball: A Job Americans Won't Do?":

When it comes to signing MLB contracts, [American] college kids lose out to cheaper foreign-born players. MLB operates camps to coach its young signees in the DR and, until the political climate got too hot, in Venezuela also.

What triggered the shift away from American ball players was an under-the-radar legislative change that eliminated visa caps for minor league players. The COMPETE Act, signed by former President George W. Bush in 2006 without congressional debate or a roll call vote, created the new "P" visa, which could be issued in unlimited numbers to baseball prospects. The "P" represents not only an opportunity for players to legally migrate to and work in the United States, but might also eventually lead to permanent residency. Bush owned the Texas Rangers from 1989 to 1994.

Before COMPETE, players had to come on H-2B visas, which were strictly limited. Since the H-2B could be used by all types of seasonal workers, applicants quickly filled up the 66,000 ceiling. The visa changes present serious challenges to American teens hoping to make the big leagues.24

The need for "international recognition" for the highest level of talent, mentioned earlier, has been transformed by this legislation and subsequent regulations into a requirement that a would-be P-1 baseball player merely needs a chit signed by an MLB executive.

Locus of Exploitation. The principal problem caused by this arrangement is the displacement of young Americans from careers that they would love to have.

The trade-off, presumably, is the ever-so-slightly higher average level of skills in the game, enhanced a bit by the access to a wider range of would-be players, on one hand, as opposed to the displacement of American youth, on the other. Some baseball purists (and team owners) may disagree, but the interests of these young, highly-skilled citizen and green card workers seems to be more important to me.

Without knowing more about the wages and working conditions in the minor leagues, I would not worry too much about the exploitation of the young DR athletes in this situation. They are all getting a chance to join the big leagues and, in the meantime, they are presumably much better paid than they would be had they stayed on the island.

I also have the impression, from reading other accounts of DR and baseball, that the incentive structures on the island, and career plans for many young males, are seriously distorted by the distant prospect of a few of them actually playing in America's major leagues.

Two Smaller Migration Streams

I do not prostrate myself in front of the Great God of the Free Market, but I must admit that each of the five occupations noted above are at least legitimate ones in our economy. There is a place for computer programmers, farm workers, landscapers, investors, and baseball players. Whether we need to bring them in from other countries, and how much they should be paid are interesting questions, but all do play authentic roles in the life of the nation.

This cannot be said for the next two streams of migrants. Each seems to be coming to the United States not because of an economic need, but because of exploitable quirks in our immigration system.

Haitian (P-3) "Culturally Unique" Artists and Entertainers

Frankly, I know very little about this odd little stream of migrants; I have never seen anything written about it and my own once extensive contacts with the Haitian community have dissipated. Intensive Google searches have been totally unproductive.

On the other hand, I once did some contract research for a non-Duvalier government of Haiti and spent three of the most depressing days of my life in pre-earthquake-ravaged Port-au-Prince. I can, as a result, totally understand why any resident of that unhappy place would want to leave by whatever means were available, legal or illegal. These remarkable pressures to emigrate must have enhanced the local use of the P-3 program.

What I do know is what can be gleaned from federal regulations for the P-3 program and from federal statistics on the extent of its use — which is proportionately huge in Haiti.

Let's start with the basic rules for the P-3 program. The full title is "P-3 artist or entertainer coming to be part of a culturally unique program". Holders of such a visa are allowed to work for pay in this field, they must have an invitation from a sponsoring organization, the initial visa is good for up to one year, and it can be renewed annually. The "initial period of stay" is the "time needed to complete the event, activity, or performance, not to exceed one year."

There are several at least nominal hurdles according to the USCIS regulations.25 They stipulate that the individual applicant has to show a contract with a U.S. sponsor, a sign-off from a union (more on that later), a description of the planned work, and documentation showing the cultural relevance of the activity.

The other data source is DoS statistics on the visa issuances; Table 4 shows the remarkably different numbers for P-1 and P-3 respectively from the two halves of the island. Clearly the culturally significant artists and entertainers are from one end of the island, and the athletes are from the other, though some Haitian athletes — 32 of them — start showing up in 2013.

My speculation is that someone in the large Haitian émigré community in the United States has figured out that the P-3 visa is a way to get some of his or her countrymen into the United States legally and has set up a system for generating the needed applications. Part of that system is the labor union element, a continuation of a tradition that relates to show business and other visas. My sense is that if one looked at these USCIS documents for the evidence of consultation with an appropriate labor union, one would find the same signature from a friendly official in one of the show business unions, time after time. Similarly, there must be a relatively routine way to obtain the "authenticity" documentation.

Can the genuine demand for "culturally unique" art and entertainment be so lopsided as the numbers in Table 4 indicate? I doubt it. Someone has clearly learned how to work the system on one side of the island, and not on the other.

I have no idea what happens to these cultural workers. To some unknown extent they must stay legally or illegally in the States, and some unknown fraction must return to Haiti. That there is some repeated travel into the states is shown by the annual admissions total in Table 3, which is about twice that of the visa issuances. Some people must use these visas more than once to enter the country.

Locus of Exploitation. Do the middlemen who operate this small, specialized program make a living out of it? Probably. Are the individual artists exploited in some way? Someone knows, but I do not.

Unlike the other worker programs noted in this report, the numbers in this one are so small, and the field so specialized, it is doubtful that many American workers are adversely affected by it.

Turkish (H-1B), Teachers of the Turkish Language in U.S. High Schools

Readers not familiar with this fairly obscure controversy might react to the heading above by thinking: "classes in Turkish were not offered in my high school days," and they would be right, they were not.

But a couple of developments in the last 20 years or so have conspired to make it possible for Turkish to be taught in some tax-supported high schools, and for there to be a small, but noticeable stream of migrants to be brought into this country to do the teaching.

The two related trends: 1) high schools have become privatized in many places; these are charter schools, which are tax-supported, but not managed by public officials; and 2) Turkish activists, led by a cleric named Fethullah Gulen, have swarmed into the charter-school business and since they control the classroom schedules they have often introduced courses in the Turkish language, even though there is zero public demand for them.

These two non-immigration-related trends have led to a specialized, and as far as I am concerned, serious abuse of the H-1B program. It is used to bring into the United States Turkish language teachers to work in the Gulen network schools.

Such a use of the program is troubling for several reasons: it means using the immigration system and local tax funds to pay alien teachers to teach a subject that no one seeks; further, it means that moneys that could have been used to pay someone (maybe a citizen) to teach a needed high school subject are diverted into an ethnic patronage job. So U.S. geometry teachers, for example, are shoved aside to make way for aliens to teach a language no one wants to study.

I found this bizarre segment of the immigration system while examining a broader topic — the Turkish intervention into the charter high school business. In what is best described as the Tammany Hall approach to education, the Turkish charter schools siphon off local tax money to start schools that say they emphasize science and math, and then contract out to various Turkish-controlled corporations, fire citizen and green card teachers, and then bring in (often accent-wielding) teachers from Turkey to replace them. Despite numerous exposés in the press, the Gulen people have enough public relations skills and political connections, often fueled by their gifts and campaign contributions to local elected officials, to stay in business.26

For an example of the latter, if you are an elected official and want a fully funded vacation in Turkey, you might talk to Mike Madigan, longtime Chicago ward leader, perpetual speaker of the Illinois State House of Representatives, chairman of the Illinois State Democratic Party, and father of Illinois' elected Attorney-General, Lisa Madigan. Mr. Madigan had four such trips provided by the Turkish-controlled Niagara Foundation over a period of four years. Perhaps coincidentally, Turkish charters in Illinois, thanks to a state statute, get 33 percent more funding than other charter schools.27

Numbers. There are no published data that I know of on the numbers of such teachers. A couple of years ago, we at CIS examined the detailed information made available by the Department of Labor on individual H-1B Labor Condition Applications to find those applications that had been filed for "teachers of Turkish" or "Turkish teachers".28 There were 59 of them in FY 2010. In subsequent years, there were approximately equal numbers of such applications. All were being hired by the Gulen schools.

Most of the thousands of teachers of Turkish nationality, brought to the states by these charter schools over the years, teach other subjects. Given the number of unemployed teachers in the country, there is, of course, no need to import them from Turkey or anywhere else.

Locus of Exploitation. The problem here, though the numbers are not massive, is that U.S.-resident high school teachers of various subjects are being pushed out of their jobs to make room for alien teachers of a subject for which there is no public demand.

There have been some media accounts that some of the new teachers from Turkey, teaching all subjects, have been pressured to contribute to the Turkish-controlled foundations that work with and promote the Gulen Schools. I do not know how widespread this is, but it certainly is in keeping with other Gulen charter school practices.

Conclusion

This has been a look at seven of the many specialized migration streams that have grown up in recent years that are dominated by members of a single ethnic group. They represent interactions among specific clauses in the immigration law, various economic and ethnic factors, and skilled middlemen. These streams are presumably a growing phenomenon and are worthy of continuing attention.

It is all much more complex than the old days when, by law, the maximum number of those would-be migrants covered by numerical limits was spelled out exactly, country by country: such as, in 1963, 17,756 for Ireland, 5,666 for Italy, and 100 each for Iceland, Iran, Iraq, and Israel.

End Notes

1 For more on this period of policy-making, see John Higham, Strangers in the Land: Patterns of American Nativism, 1860-1925, Rutgers University Press, 2nd edition, 1988; particularly chapter 11.

2 The oldest Congressional Directory in my collection, that of February 1920, appears to list only one member of Congress with a Hispanic name. He was Benigno Cardenas Hernandez, New Mexico's only member of the House, and a Republican. Both of that state's senators that year were Anglos, as were all the others, in both houses, from the Southwest.

3 Estimates vary, but there were about 1.8-2.0 billion residents of the Eastern Hemisphere at the time, and less than 100 million from the non-U.S. parts of the Western Hemisphere. In fact, in 1920 it appears that a majority of the population of the hemisphere lived in the United States; currently something like 30 percent of people in the Western Hemisphere are residents of the United States.

4 For a useful introduction to this subject, see Jessica Vaughan, "Shortcuts to Immigration: The 'Temporary' Visa Program is Broken", Center for Immigration Studies Backgrounder, January 2003.

5 None of these programs are related to multi-national agreements, but several sets of visas are based on bi-national agreements: TN and TD visas go to some Canadian and Mexican nonimmigrants under the North American Free Trade Agreement and there are E-1 and E-2 visas for treaty traders and treaty investors from specific nations.

6 For more on this subject, see Steven A. Camarota and Karen Zeigler, "Is There a STEM Worker Shortage?", Center for Immigration Studies Backgrounder, May 2014.

7 In many democracies, all of these steps are handled by a single agency, a ministry of immigration.

8 On re-reading my own estimates, I see I have defined the H-1B population broadly to include several tens of thousands of F-1 students on their path to H-1B status, and several more tens of thousands of H-1B alumni who have recently moved to green card status. See David North, "Technical Note: The Estimate of about 650,000 H-1Bs as of 9/30/09", Center for Immigration Studies blog, January 28, 2011.

9 See "Visa Bulletin For October 2014", U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Consular Affairs, September 8, 2014.

10 See David North, "Looking at the H-1B Process Through the Eyes of the Participants", Center for Immigration Studies Memorandum, April 2010.

11 See "2014 H1B Visa Reports: Top 100 H1B Visa Sponsors", Myvisajobs.com.

12 See my most recent blog on the subject, "H1-B News: Whistleblower Jack Palmer Goes After Infosys Again", October 7, 2014.

13 Ron Hira, "Bridge to Immigration or Cheap Temporary Labor", EPI Briefing Paper #257, Economic Policy Institute, February 17, 2010.

14 I played a supporting role in this process, in 1965 and 1966, as Assistant for Farm Labor to the U.S. Secretary of Labor, the late W. Willard Wirtz.

15 This initial recruitment exploitation is particularly problematic in Jamaica, where entrance to the H-2A program is controlled by rural members of Parliament, and these patronage-selected workers can be admitted to the United States without the need for an American visa. For more on these strange arrangements, see, my blog on the subject, "Our Visa System, or the Little Dutch Boy in Reverse", May 21, 2014.

16 In FY 2013 there were 204,577 admissions in the H-2A program and 104,993 in H-2B, according to Table 32 in the Yearbook of Immigration Statistics, 2013, Department of Homeland Security, 2014.

17 See "Annual Report, October 1, 2011 – September 30, 2012", U.S. Department of Labor, July 2013.

18 See David Seminara, "Dirty Work: In-Sourcing American Jobs with H-2B Guestworkers", Center for Immigration Studies Backgrounder, January 2010.

19 For more information on this program, see David North, "The Immigrant Investor (EB-5) Visa", Center for Immigration Studies Backgrounder, January 2012. It was written before the recent expansion in the program was fully visible.

20 See Peter Elkind and Marty Jones, "The dark disturbing world of the visa-for-sale program", Fortune, July 24, 2014.

21 See my blog, "It's Beginning to Look Like Watergate in South Dakota EB-5 Case", Center for Immigration Studies, December 4, 2013.

22 See my blog, "No More EB-5 Visas for Chinese Nationals — For a Month", Center for Immigration Studies, August 29, 2014.

23 The data come from the previously cited Yearbook of Immigration Statistics, 2013, Table 32. There were 6,992 nonimmigrant worker admissions from the Dominican Republic that year; of these, 3,481 were in the P categories; comparable numbers for Haiti were 750 and 439.

24 See Joe Guzzardi, "Playing Major League Baseball: A Job Americans Won't Do?", Californians for Population Stabilization, October 26, 2012.

25 See "P-3 Artist or Entertainer Coming to Be Part of a Culturally Unique Program", USCIS, January 28, 2011.

26 Note that the Gulen schools have different names in different places. They are Harmony Schools in Texas, Concept Schools in Ohio, etc. Here is a sampling of local media coverage: "Harmony schools causing discord", San Antonio Express News, September 15, 2011; "Audits for 3 Georgia Schools Tied to Turkish Movement", The New York Times, June 5, 2012; "U.S. charter-school network with Turkish link draws federal attention", Philadelphia Inquirer, March 20, 2011; "Ohio taxpayers provide jobs to Turkish immigrants through charter schools", Akron Beacon-Journal, July 6, 2014; and "19 Charter schools to be investigated for years of misconduct", The Columbus Dispatch, July 16, 2014. The headlines above reflect the tone and the content of the coverage.

27 For more on Madigan's relations with the Turkish schools see my blog (and the links therein), "Turkish H-1B Abuser Continues Tammany Hall Methods in the U.S.", Center for Immigration Studies, January 23, 2014. For more on Madigan's impressive political credentials, see his biography on Wikipedia.

28 These data can be accessed through the Foreign Labor Certification Data Center.