With the Biden administration showing no backbone toward illegal migration, one wonders what would happen to international migration if we simply let in anyone who wanted to come?

That may seem to be a far-fetched question and a totally theoretical one, but in our multilayered immigration policy we actually have been experimenting with such a system for more than 30 years on a small scale; a little open-borders laboratory with some real, live results, if you will.

The experiment shows that there would be massive numbers of immigrants, more than we could possibly handle.

The mini-open-borders policy that we have is unknown to most Americans; it apples only to the residents of three Central Pacific sets of islands, which have been, in sequence, Spanish, German, Japanese, and American colonies, and are now the quasi-independent nations of the Republic of the Marshall Islands, the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM), and the Republic of Palau. (I visited the first two while working for the U.S. Department of Interior.)

The policy is simplicity itself: If you are a native citizen of any of these little nations you can come to the U.S. as a nonimmigrant needing no visa; you can obtain a work permit here and stay for the rest of your life. That’s a totally open door. It is spelled out in the somewhat different Compacts of Free Association with each of those nations signed in 1985.

Each nation has an embassy in D.C., and each has a vote in the General Assembly of the United Nations; the U.S. provides for the defense of these nations, and financial subsidies. They, in turn, have given us access to military bases, such as our current rocket base in the FSM, and let us nuke Bikini (in the Marshalls) to smithereens in a weapons test shortly after the end of WWII.

Our policy to let them all in was a deliberate one. I remember waiting for a Senate elevator one day in the 1980s and finding that then-Sen. Alan Simpson (R-Wyo.), a limited-immigration advocate before whom I had testified, was waiting, too. I asked him about our policy on admitting the islanders to the U.S. and he said “there aren’t many of them, so we are going to set no limits on their admission” or words to that effect. The now much-missed Simpson in those days was then either chairman of the Senate’s immigration subcommittee or its ranking Republican.

So what has happened to that experiment?

To quote a 2014 article by Michael Duke of the Migration Policy Institute:

Approximately one-third of the population of the Republic of the Marshall Islands, a series of islands and atolls in the Pacific, has relocated to the United States with Hawaii and Guam key destinations as well as — perhaps surprisingly — Arkansas.

At that time, there were about 53,000 residents of the Marshall Islands, and about 22,400 in the States.

We know from world-wide polling that some 158 million people said five years ago that they would like to move to the U.S., and that number today is probably much higher. While 158 million would exceed our annual legal migration by a factor of about 158 to one, it is still only about 2 percent of the world’s population.

In the reality of the Marshall Islands, those actually migrating to the U.S. — not just telling a pollster that they would like to —was something like 30 percent of the islands’ population.

Clearly, we cannot absorb either 2 percent or 30 percent of the world’s population and the laboratory experiment, if you will, with the Marshalls shows how devastating a broader open-borders policy would be. More of us should be spreading the word that the mass movement of the Marshallese is a predictor of what’s to come if we do not have a strong policy at our borders.

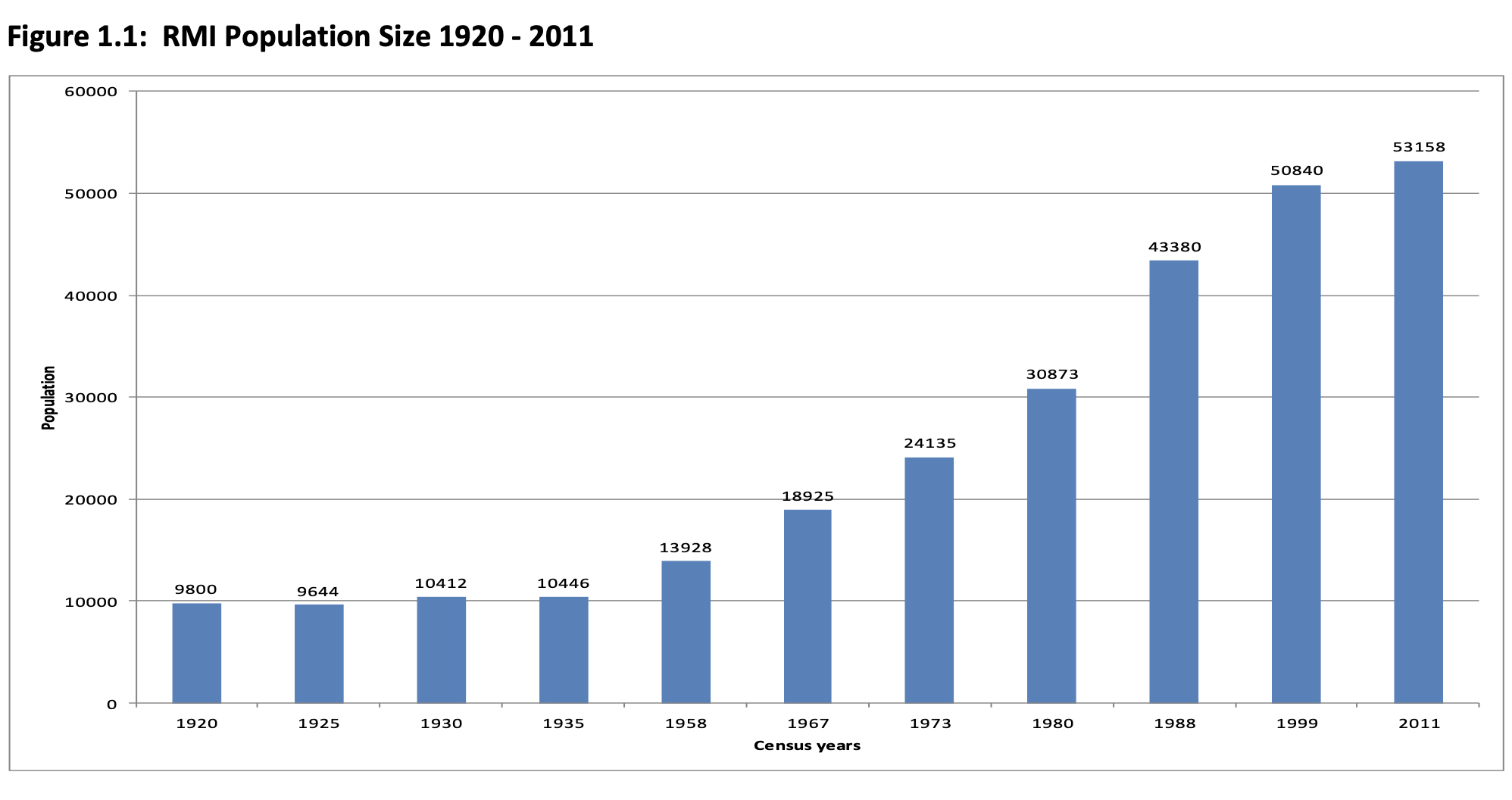

Population Data for the Marshalls. Figure 1.1 in the 2011 census of these islands shows, while not saying so, the population growth, or the lack of it, under Japanese and American rule. In the figure, we see that in the 1920-1935 period, with Japan in control, the population was stabilized at around 10,000, growing at the rate of only about 44 people per year, or about 0.4 percent annually. In the 1958-2011 period, the population exploded from 13,928 in 1958 to 53,158 in 2011, an average increase of 740 a year. During these years the U.S. brought a lot of money to these islands, but no (or no successful) birth control programs.

|

The other two associated states (Palau and FSM) have sent large numbers of migrants to the U.S. under the compacts, but smaller, percentage-wise delegations than from the Marshalls, with geography playing a key role in these ratios. The population per square mile data shows the Marshalls are far more over-populated than the other two: 349 for the Marshalls, 153 for FSM, and 46 for Palau. Further, the Marshalls consist of only low-lying atolls and islands, while the other two nations have many high islands, meaning that rising sea levels are less threatening than in the Marshalls. And only the Marshalls have lost whole islands, such as Bikini, to bomb testing.

The Arkansas Destination. The largest concentration of Marshallese in the 48 states is in or near Springdale, Ark., home to Tyson Foods. As an Oxfam report put it;

The booming poultry industry in America is built on the backs of workers on the processing line; they earn low wages of diminishing value, suffer high rates of injury and illness, and have little voice or dignity in their labor.

No swaying palm trees in Springdale, and no easy access to lovely beaches, just the bloody business of killing and dismembering chickens. So this docile foreign workforce, taking advantage of our open-borders experiment, winds up being taken advantage of by one of America’s biggest corporations.

It is ever thus.