U.S. drug overdose deaths exceeded 100,000 for the one-year period ending April 2021, and show no signs of slowing down. While the White House has promised “bold, new solutions aimed at keeping Americans alive”, the best response to the U.S. overdose epidemic is to slow the flood of illicit drugs into the country. And as CBP statistics out of Yuma, Ariz., show, that means freeing up Border Patrol agents to stop the drug flow by discouraging migrants from entering the United States illegally.

America’s Drug Crisis — and Mexico’s Increasingly Weak Response. The CDC estimates that 100,306 Americans died from drug overdose deaths between April 2020 and April 2021, a 28 percent increase over the same period one year before. More than three-quarters of those deaths were associated with opioids, which include illegal substances like heroin and fentanyl, as well as prescription drugs such as oxycodone, hydrocodone, codeine, and morphine.

Fentanyl is particularly deadly — it’s 50 to 100 times more potent than morphine, and two milligrams can kill you (depending on your body weight and tolerance). Worse, as the DEA explains, fentanyl is being mixed with other illicit drugs to increase their potency. Adolescents have even started vaping fentanyl.

A bipartisan panel of experts recently looked into the problem and determined Mexico is the main source of fentanyl and its analogues today, a change from the past when the drug was primarily mailed into the United States from China.

Not surprisingly, the panel concluded, cartels and transnational criminal organizations (TCOs) are the ones who are smuggling those synthetic opioids from Mexico to the United States.

Worse, it explained that authorities south of the border are increasingly unhelpful in stopping drug trafficking to the United States: “The Mexican government, in part out of self-preservation and in part because the trafficking problem transcends current law enforcement capacity, recently adopted a ‘hugs, not bullets’ approach to managing the transnational criminal groups.”

That’s despite the fact that drug trafficking in Mexico “contributes to corruption, challenges state security, and fuels extreme violence” there.

How Drugs Enter the United States. Most illegal drugs cross the border into the United States in one of two ways: Hidden in cars and among legal goods entering the United States through the ports of entry, or across the 1,954-mile land border between the ports of entry.

You will hear “experts” tell you that “virtually all” illicit drugs enter the United States through the legal ports of entry. That may be true, and the ports are where most drugs are seized, but respectfully, saying that is akin to proving a negative, in this instance quantifying the amount of drugs that aren’t seized at the border, but instead flood American streets.

Understand that cartels and TCOs are rational economic actors. They will move product in the easiest way possible with the highest likelihood that their drugs can make it to markets in the United States.

CBP officers at the ports have many tools at their disposal to find and seize contraband, including illicit narcotics. To get drugs into the United States through a port, smugglers must submit to questioning, possible physical searches, and canine sniffs, and if officers at the ports have any questions, they can refer drivers and pedestrians to secondary inspection where officers are trained to get to the truth.

If they do have are any concerns, CBP officers can physically (and occasionally extremely intrusively) search vehicles and use large X-ray machines to check out suspected loads.

Border Patrol agents between the ports, however, lack most of those tools, and more problematically must actively find smugglers before they can search them. Again, the Southwest border is nearly 2,000 miles long, and in many places is rugged and desolate — there are plenty of places to hide until the heat dies down.

Border Patrol’s Capacity to Stop Drugs at the Southwest Border. Massive waves of illegal immigrants sap Border Patrol’s capacity to stop drugs from entering the United States.

At the end of FY 2020, Border Patrol had just fewer than 16,900 agents on duty at that border. Agents work 50-hour weeks, which means that at any given time, there are about 5,023 Border Patrol agents on the line.

Simply looking at the statistics, that means that under the best of circumstances, there is one agent for every .39 miles of the Southwest border, an area just less than seven football fields in length (and hundreds of miles in depth). That is a lot of space for one agent to patrol, but Border Patrol is hardly operating under the best of circumstances of late.

Border Patrol apprehended more illegal migrants at the Southwest border in FY 2021 than in any fiscal year in history. Once caught, those migrants must be processed, detained, housed, and often fed and cared for. The larger the number of migrants apprehended in a given area, the more agents who must be pulled off the line and assigned to those non-patrol tasks.

A (separate) bipartisan panel report in April 2019, looking at a much smaller surge of aliens that year, reported that 40 percent of Border Patrol’s resources were absorbed in performing such duties. That meant that only 60 percent of agents were available to stop other migrants, drugs, and contraband from entering the United States. Given how bad the border disaster has become, that means that even fewer agents are now available to perform those duties.

That’s bad, but it gets worse. In a September letter to Congress, former Border Patrol Chief Rodney Scott explained that TCOs were “scripting and controlling” migrant entries “to create controllable gaps in border security. These gaps are then exploited to easily smuggle contraband, criminals, or even potential terrorists into the U.S. at will.”

Migrants and Drugs in Yuma Sector. To understand how all of this has played out in the real world, you need look no further than the Border Patrol’s Yuma sector.

All nine Border Patrol sectors at the Southwest border have taken it on the chin in attempting to respond to the migrant surge that has followed in the wake of the inauguration of President Joe Biden, but none of the other ones saw an increase in apprehensions like Yuma.

In FY 2020, the 784 agents in Yuma sector apprehended just over 8,800 illegal migrants. By the end of FY 2021, agents in Yuma made nearly 114,500 apprehensions — more than 13 times as many as they had the year before (a surge that has continued unabated into FY 2022).

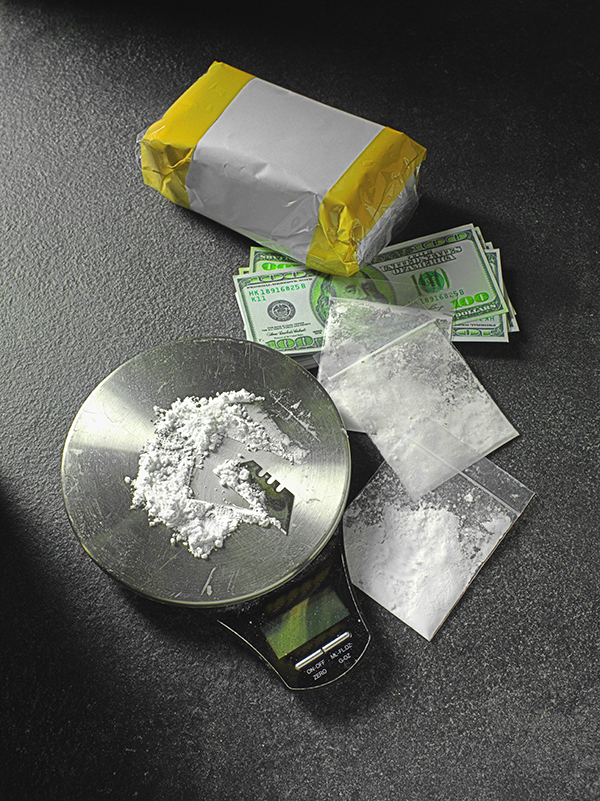

Which leads me to the drugs. Agents in the Yuma sector seized nearly 6,750 pounds of drugs in FY 2020, including more than 84 pounds of cocaine, 18.5 pounds of heroin, more than 1,900 pounds of methamphetamine, and 107.48 pounds of fentanyl — the latter enough to kill up to 24,376,034 Americans.

By the end of FY 2021, a year in which Border Patrol agents there apprehended more than 13 times as many illegal migrants as they had the previous fiscal year, drug seizures in the Yuma sector fell more than 70 percent to 2,021 pounds.

That included 1,158 pounds of meth, 36.5 pounds of cocaine, less than an eighth of a pound of heroin, and just over 85 pounds of fentanyl. In other words, Border Patrol meth apprehensions in Yuma fell just less than 40 percent, cocaine apprehensions fell more than 57 percent, heroin apprehensions fell 99.3 percent, and fentanyl seizures dropped more than 20 percent in a year.

It is possible that the cartels and TCOs decided to give the agents in Yuma a break by sending fewer drug loads across the border there. Possible, but highly unlikely. In fact, given the CDC data, the flow of drugs has simply increased along the Southwest border in the past few years.

The Sinaloa cartel, which has been described as “the most powerful drug trafficking organization in the Western Hemisphere”, is responsible for the majority of drugs that cross the border into Arizona.

As the Treasury Department reported in December: “The Sinaloa Cartel controls drug trafficking activity in key regions throughout Mexico, especially along the Pacific Coast. From these strategic points, the Sinaloa Cartel traffics multi-ton quantities of illicit drugs, including fentanyl and heroin, into the United States.”

There is no reason to doubt that assessment, which raises the question of why drug seizures in the Yuma sector — which has jurisdiction over 126 miles of the border — dropped so significantly in FY 2021.

Here’s the answer: Drug seizures in the Yuma sector fell more than 70 percent between FY 2020 and FY 2021 because apprehensions of illegal migrants there increased by more than 1,200 percent during the same period. If the Biden administration is looking for “bold, new solutions” to cut U.S. overdose deaths, it can start by deterring illegal migration.